The Maya Calendar: Cycles of Time and Prophecy

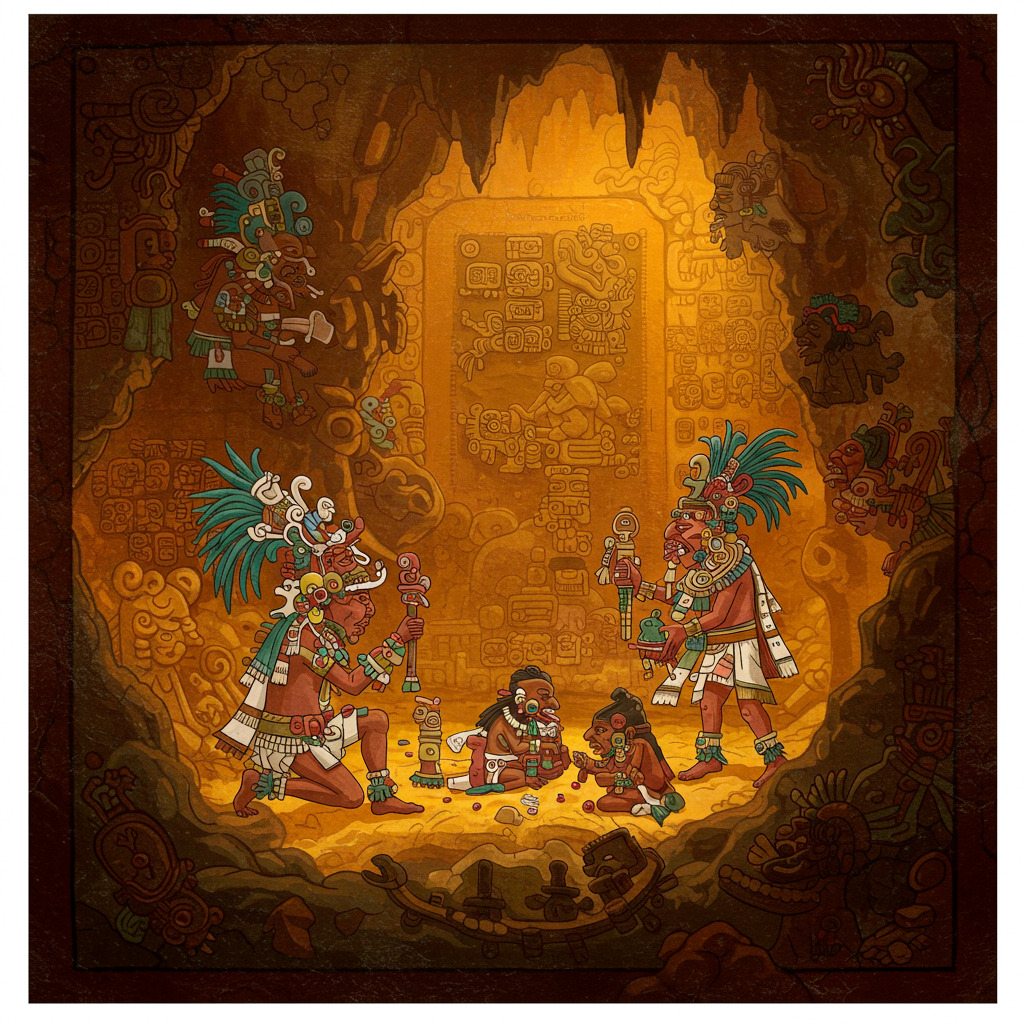

The Maya civilization, renowned for its remarkable achievements in architecture, mathematics, and astronomy, developed an intricate calendar system that reflects their profound understanding of time and the cosmos. This calendar not only served practical purposes, such as agricultural planning and ritual observances, but also played a pivotal role in their cultural and spiritual life. As we delve into the Maya calendar, we uncover a sophisticated framework that reveals how the ancient Maya perceived the cyclical nature of time and its influence on their society.

At the heart of this fascinating system are the Tzolk'in and Haab' cycles, which together create a complex interplay of days, months, and years. The Maya's unique approach to timekeeping allowed them to track celestial events with impressive accuracy, establishing a connection between the heavens and human affairs. Furthermore, the calendar is steeped in rich symbolism and prophecy, prompting both reverence and intrigue among scholars and enthusiasts alike.

In this exploration, we will unravel the historical context and significance of the Maya calendar, examine its structure and concepts of time, and discuss the prophecies and beliefs that emerged from this ancient system. Join us on a journey through the cycles of time and prophecy that defined a civilization that continues to captivate our imagination.

Understanding the Maya Calendar

The Maya civilization, renowned for its advanced knowledge of astronomy and mathematics, developed a complex calendar system that not only served practical purposes but also held deep cultural significance. Understanding the Maya calendar requires an exploration of its historical context, structural intricacies, and the interwoven cycles of time that defined Maya life. This section will delve into these aspects, providing insight into how the Maya perceived time and the importance they placed on their calendar system.

Historical Context and Significance

The Maya civilization flourished in Mesoamerica, particularly in present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador, from around 2000 BCE until the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. The development of the calendar was not merely a means of tracking days but was intricately linked with the Maya’s agricultural practices, religious rituals, and social organization. As the Maya transitioned from nomadic to settled agricultural societies, the need for a reliable method of timekeeping became paramount.

Maya society was deeply religious and viewed time as a cyclical phenomenon rather than a linear progression. This perspective influenced their calendar system, which encompassed multiple interrelated cycles that governed various aspects of life. The calendar was not only a tool for agriculture but also a means of aligning their spiritual practices with the cosmic order. The cycles of the calendar were believed to affect the fate of individuals and the community as a whole, thus making it a central aspect of Maya spirituality.

Furthermore, the significance of the calendar extended to political power. Rulers often used calendrical events to legitimize their authority, claiming divine sanction for their reign based on auspicious dates. Major events such as wars, marriages, and ceremonies were meticulously planned around the calendar, reflecting its integral role in governance and societal structure.

Structure of the Maya Calendar System

The Maya calendar system is composed of several interlocking cycles, the most notable of which are the Tzolk'in, Haab', and the Long Count. Each of these calendars serves a distinct purpose and operates on different time scales, yet they are interconnected, creating a complex framework for understanding time.

The Tzolk'in is a 260-day calendar that consists of 20 periods of 13 days, each associated with a specific deity and meaning. This cycle is thought to be linked to the agricultural calendar, particularly the gestation period of maize, which was a staple crop for the Maya. Each day in the Tzolk'in carries unique significance, influencing events and decisions. For instance, certain days are considered auspicious for specific activities, such as planting or conducting rituals.

The Haab', on the other hand, is a 365-day solar calendar divided into 18 months of 20 days each, plus an additional month of 5 days known as the Wayeb’. This calendar aligns more closely with the solar year and was used primarily for agricultural and civil purposes. The Haab' months are rich in ceremonial significance, with each month dedicated to different deities and agricultural cycles.

Finally, the Long Count calendar provides a way to track longer periods of time, allowing the Maya to record historical events and cycles over millennia. It consists of a series of cycles that include the baktun (approximately 394 years), katun (approximately 20 years), tun (365 days), uinal (20 days), and k'in (one day). The Long Count was essential for historical record-keeping and played a significant role in the Maya’s understanding of their past and future.

| Calendar | Cycle Length | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Tzolk'in | 260 days | Ritual and agricultural events |

| Haab' | 365 days | Civil and agricultural calendar |

| Long Count | Varies | Historical record-keeping |

This intricate structure allowed the Maya to maintain a comprehensive understanding of time, linking daily life with cosmic events, agricultural cycles, and historical narratives.

The Tzolk'in and Haab' Cycles

The Tzolk'in and Haab' cycles are crucial to understanding the Maya calendar's functionality. The interplay between these two calendars creates a unique system where every day is identified by a combination of a number (from one to thirteen) and a name (from a set of twenty day names). This combination results in a total of 260 unique days in the Tzolk'in calendar.

In contrast, the Haab' cycle runs concurrently, providing a solar calendar that aligns with the seasons. The 365-day year is divided into eighteen months of twenty days each, followed by the short month of Wayeb', which consists of five days considered unlucky or dangerous. The combination of the Tzolk'in and Haab' cycles results in a 52-year period known as the Calendar Round, where each day in the Tzolk'in corresponds with a specific day in the Haab'. This cyclical nature reinforces the Maya belief in the interconnectedness of all life and the universe.

During the Calendar Round, various festivals, rituals, and agricultural activities are timed to coincide with significant days in both cycles. For example, particular days in the Tzolk'in may be seen as auspicious for planting or harvesting, while certain Haab' months may be dedicated to specific deities or agricultural practices. This synchrony highlights the importance of both calendars in daily life and spiritual practices.

Moreover, the Tzolk'in and Haab' cycles were not merely theoretical constructs but were deeply embedded in the Maya's social and political frameworks. The ruling elite often utilized this calendrical knowledge to establish power and control, organizing events and ceremonies that reinforced their status. For instance, the timing of royal births, marriages, and funerals was meticulously planned according to the calendar, ensuring that these events occurred during auspicious periods.

In summary, the Maya calendar is a sophisticated system that reflects the civilization's understanding of time as a cyclical phenomenon. It intertwines agricultural, spiritual, and political aspects of Maya life, reinforcing the belief in the interconnectedness of all things. The Tzolk'in and Haab' cycles, along with the Long Count, create a comprehensive framework for tracking time, shaping the Maya worldview, and guiding their daily practices.

As we explore the Maya calendar further, it becomes evident that understanding this intricate system provides valuable insights into the culture, beliefs, and history of one of the most remarkable civilizations in human history.

Maya Calendar and Timekeeping

The Maya civilization, known for its remarkable achievements in astronomy, mathematics, and art, developed a sophisticated system of timekeeping that was intricately linked to their cultural and spiritual beliefs. Time was not merely a measurement for the Maya; it was a cyclical entity that influenced their daily lives, agricultural practices, and religious ceremonies. This section explores the concepts of time in Maya culture, the Long Count calendar, and how the Maya calendar correlates with modern calendars.

Concepts of Time in Maya Culture

In Maya culture, time was perceived as a cyclical phenomenon, encompassing the notions of creation, destruction, and renewal. The Maya believed that past, present, and future were interconnected, and their understanding of time was deeply influenced by astronomical observations. The cycles of celestial bodies, particularly the sun, moon, and planets, were critical in shaping their calendar systems.

Maya timekeeping was not linear; rather, it was composed of repeating cycles of varying lengths. One of the most significant concepts in Maya timekeeping was the idea of "k’atun," a period of approximately 20 years, which was part of the larger "baktun," lasting around 394 years. These long cycles were integral to their cosmology and were often associated with significant historical events or prophecies.

The Maya also had a unique relationship with the concept of duality, which was reflected in their calendar systems. The interplay between different cycles, such as the Tzolk’in and Haab’, illustrated the Maya belief in the balance of opposites. For instance, while the Tzolk’in represented spiritual and religious time, the Haab’ was aligned with agricultural and social activities. This duality underscored the importance of harmonizing various aspects of life, emphasizing that time was not merely a series of dates but a living entity that required respect and understanding.

The Long Count Calendar Explained

The Long Count calendar was a significant component of the Maya calendar system, designed to track longer periods of time. It was essential for recording historical dates, prophecies, and significant events. The Long Count calendar's structure consisted of a series of cycles, each composed of various units of time, including the baktun, k’atun, tun, uinal, and k’in.

| Time Unit | Duration |

|---|---|

| K’in | 1 day |

| Uinal | 20 k’in (approx. 20 days) |

| Tun | 18 uinal (approx. 360 days) |

| K’atun | 20 tun (approx. 7,200 days) |

| Baktun | 20 k’atun (approx. 394 years) |

The Long Count calendar starts from a base date, which is believed to be August 11, 3114 BCE in the Gregorian calendar. This date marked the mythical creation of the world, according to the Maya. Each Long Count date is expressed in a sequence of five numbers representing the number of baktun, k’atun, tun, uinal, and k’in. For example, a date written as 13.0.0.0.0 indicates 13 baktun, 0 k’atun, 0 tun, 0 uinal, and 0 k’in.

The Long Count was crucial for the Maya to articulate their history, as it allowed them to document events and align them with their cosmological beliefs. This calendar was also vital for predicting future cycles and understanding their place in the universe. For the Maya, these calculations were not merely academic; they were a means of connecting their present with the divine order of time established by the gods.

Correlation with Modern Calendars

Understanding the Maya calendar system's correlation with modern calendars is essential for comprehending how the Maya viewed time in relation to our current understanding. The Maya calendar does not align perfectly with the Gregorian calendar, which is widely used today. However, scholars have developed correlation methods to translate Maya dates into the Gregorian system, allowing for a better understanding of historical events and prophecies in the context of modern timekeeping.

One of the most widely accepted correlation methods is the GMT (Goodman-Martinez-Thompson) correlation, which suggests that the Long Count date of 13.0.0.0.0 corresponds to December 21, 2012, in the Gregorian calendar. This particular date gained significant attention due to its association with various prophecies predicting the end of the world or a transformative change in consciousness. While many interpretations of this date emerged, it is crucial to note that the Maya did not view it as an apocalyptic end but rather as a transition into a new cycle of time.

The complexities of correlating Maya dates with modern calendars arise from the differing structures and purposes of each system. While the Gregorian calendar is linear and solar-based, the Maya calendar revolves around multiple interlocking cycles, each serving different cultural and agricultural purposes. The Tzolk’in, a 260-day sacred calendar, was primarily used for religious and ceremonial events, while the Haab’, a 365-day civil calendar, governed agricultural activities. The interplay of these calendars reflects the Maya's intricate understanding of time and its cycles.

Another significant aspect of the Maya calendar's correlation with modern timekeeping is the observation of astronomical events. The Maya were skilled astronomers, capable of predicting eclipses, solstices, and the movements of planets with remarkable accuracy. Their observations were integral to their calendar system, influencing agricultural cycles, religious ceremonies, and social organization. For instance, certain agricultural activities would commence based on specific celestial events, reflecting their deep connection to the cosmos.

Moreover, the Maya calendar's relationship with modern timekeeping raises questions about how different cultures perceive and measure time. While Western societies often view time as a commodity to be managed, the Maya's cyclical perspective emphasizes a more holistic understanding of time as a living entity intertwined with cultural and spiritual practices. This duality showcases the richness of indigenous knowledge systems and challenges us to reconsider our relationship with time.

In conclusion, the Maya calendar and its sophisticated system of timekeeping serve as a testament to the civilization's profound understanding of the cosmos and its cyclical nature. Through the exploration of concepts of time in Maya culture, the Long Count calendar, and its correlation with modern calendars, we gain insight into how the Maya navigated their world, interpreted celestial events, and integrated their beliefs into their daily lives. The Maya calendar remains a vital aspect of their cultural heritage, continuing to inspire fascination and study among scholars and enthusiasts alike.

Prophecies and Beliefs Associated with the Maya Calendar

The Maya civilization, one of the most sophisticated cultures in Mesoamerica, had an intricate understanding of time and its cycles. Their calendar system was not just a method for tracking time but also a fundamental part of their belief system, weaving together their spirituality, agriculture, and societal organization. Among the various aspects of the Maya calendar, prophecies and beliefs stand out as particularly fascinating, as they reveal how the ancient Maya interpreted the world around them and predicted future events. This section delves into the major prophecies associated with the Maya calendar, the influence of astronomical events on these beliefs, and the cultural impact these calendar predictions had on both ancient and modern societies.

Major Prophecies and Their Interpretations

One of the most notable aspects of the Maya calendar is its connection to prophecies, especially those linked to the end of cycles. The most famous prophecy, which gained substantial media attention in the early 21st century, was the so-called "end of the world" prediction for December 21, 2012. This date marked the end of a significant cycle in the Maya Long Count calendar, specifically the completion of the 13th Bak'tun, a period of approximately 394 years. Many interpretations suggested that this date signified a cataclysmic event, leading to widespread speculation about apocalyptic scenarios.

However, scholars and Maya descendants clarified that the end of the 13th Bak'tun was not viewed as an end in a destructive sense but rather as a transition to a new cycle. The ancient Maya believed that time was cyclical, and the completion of one era naturally led to the beginning of another. In this context, December 21, 2012, was celebrated as a time of renewal and reflection rather than destruction. This cyclical view of time is central to understanding Maya cosmology, where past, present, and future coexist in a perpetual loop.

Another significant prophecy in Maya belief is linked to the "Popol Vuh," the sacred book of the K'iche' Maya. This text contains creation myths and historical narratives that outline the origins of humanity and the gods' interactions with people. The Popol Vuh discusses various cycles and their endings, emphasizing that human behavior and cosmic events are interconnected. The Maya believed that the actions of rulers and common people could influence the gods, and thus, their choices could lead to favorable or unfavorable outcomes during these cycles.

Furthermore, the Maya calendar was closely tied to agricultural cycles, which were crucial for their subsistence. The cycles of planting and harvesting were often associated with prophecies about prosperity and disaster. For instance, a poor harvest could be interpreted as a sign of displeasure from the gods, prompting rituals to appease them. In this way, prophecies were not merely predictions but also calls to action, urging communities to align their practices with the rhythms of nature and the cosmos.

The Role of Astronomical Events

Astronomical events played a vital role in the Maya's understanding of time and prophecies. The Maya were skilled astronomers, meticulously observing celestial bodies and their movements. They tracked the cycles of the sun, moon, and planets, particularly Venus, which held special significance in their mythology and calendar system. The "Dresden Codex," one of the few surviving pre-Columbian books, contains detailed astronomical tables that predict the appearances of celestial bodies and their associated omens.

One of the most critical astronomical events in Maya prophecy was the appearance of planetary alignments, eclipses, and solstices. These events were viewed as powerful omens that could signify significant changes in the world, often interpreted as messages from the gods. For example, a solar eclipse could be seen as a warning of impending disaster or a sign of divine intervention. The timing of these events was crucial; the Maya would often plan religious ceremonies and rituals around them to ensure harmony with the cosmos.

The Maya also placed great importance on the "Tzolk'in," the 260-day sacred calendar that is believed to be linked to the cycles of human gestation and agricultural practices. The intersections of the Tzolk'in with the solar year (Haab') and the Long Count created a complex web of timekeeping that allowed the Maya to make predictions about the future. This system reinforced the idea that human events were interwoven with celestial cycles, thus emphasizing the importance of living in accordance with the universe's rhythms.

Cultural Impact of Calendar Predictions

The cultural impact of the Maya calendar and its associated prophecies cannot be overstated. The calendar shaped the Maya worldview, influencing everything from governance to agriculture to religious practices. Leaders often used the calendar to legitimize their rule, correlating their reigns with significant cosmic events. For instance, a ruler born on an auspicious day might be seen as divinely chosen, enhancing their authority and the social cohesion of the community.

Moreover, the calendar's predictions and prophecies were integral to ceremonies and rituals. Festivals often coincided with significant dates in the calendar, celebrating gods and ancestors while seeking to ensure agricultural success and societal harmony. The Maya believed that by performing rituals aligned with the calendar, they could influence the natural world and secure the favor of the gods.

In contemporary times, the legacy of the Maya calendar continues to resonate, particularly among the descendants of the Maya who still observe traditional beliefs and practices. Many modern Maya communities celebrate the completion of the cycles, reflecting on their significance and integrating them into their cultural identity. This revival of interest in the calendar has sparked discussions about cultural heritage, identity, and the importance of indigenous knowledge in a rapidly changing world.

The fascination with the Maya calendar has also permeated popular culture, often distorted by sensationalist interpretations. The apocalyptic predictions surrounding 2012, for instance, highlighted a broader trend where ancient wisdom is sometimes misappropriated for commercial or entertainment purposes. This underscores the importance of approaching the Maya calendar with respect and a nuanced understanding of its cultural significance.

In conclusion, the prophecies and beliefs associated with the Maya calendar reflect a deep understanding of time as a cyclical phenomenon intertwined with human existence and the cosmos. The major prophecies, the role of astronomical events, and the cultural impact of calendar predictions demonstrate how the Maya viewed their world and their place within it. As we continue to explore the legacy of the Maya civilization, it is essential to recognize and honor their profound insights into the nature of time and existence.